Describe The Makeup Of The Supreme Court In 1857?

| Dred Scott v. Sandford | |

|---|---|

Supreme Courtroom of the United States | |

| Argued February 11–14, 1856 Reargued December xv–18, 1856 Decided March 6, 1857 | |

| Full example name | Dred Scott v. John F. A. Sandford[a] |

| Citations | 60 U.Southward. 393 (more) 19 How. 393; fifteen Fifty. Ed. 691; 1856 WL 8721; 1856 U.S. LEXIS 472 |

| Decision | Opinion |

| Instance history | |

| Prior | Judgment for defendant, C.C.D. Mo. |

| Holding | |

Judgment reversed and accommodate dismissed for lack of jurisdiction.

| |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Taney, joined by Wayne, Catron, Daniel, Nelson, Grier, Campbell |

| Concurrence | Wayne |

| Concurrence | Catron |

| Concurrence | Daniel |

| Concurrence | Nelson, joined by Grier |

| Concurrence | Grier |

| Concurrence | Campbell |

| Dissent | McLean |

| Dissent | Curtis |

| Laws applied | |

| U.South. Const. improve. V; U.Due south. Const. art. IV, § 3, cl. 2; Strader five. Graham; Missouri Compromise | |

| Superseded past | |

| U.Due south. Const. amends. 13, 14, XV; Civil Rights Act of 1866; Kleppe v. New Mexico (1976) (in role)[2] | |

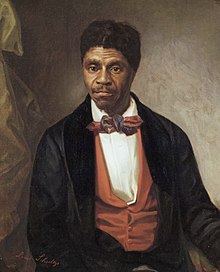

Dred Scott v. Sandford ,[a] 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court in which the Court held that the United States Constitution was not meant to include American citizenship for people of African descent, regardless of whether they were enslaved or gratis, so the rights and privileges that the Constitution confers upon American citizens could non apply to them.[3] [4] The Supreme Court's decision has been widely denounced, both for how overtly racist the decision was and its crucial part in the offset of the American Civil State of war four years afterward.[5] Legal scholar Bernard Schwartz said that it "stands first in any list of the worst Supreme Court decisions". Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes called it the Court's "greatest self-inflicted wound".[6] Historian Junius P. Rodriguez said that information technology is "universally condemned every bit the U.Due south. Supreme Courtroom'southward worst decision."[7] Historian David Thomas Konig said that information technology was "unquestionably, our court's worst decision e'er."[viii]

The decision was fabricated in the instance of Dred Scott, an enslaved black man whose owners had taken him from Missouri, a slave-holding land, into Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory, where slavery was illegal. When his owners later on brought him back to Missouri, Scott sued in court for his freedom and claimed that because he had been taken into "free" U.S. territory, he had automatically been freed and was legally no longer a slave. Scott sued first in Missouri state court, which ruled that he was still a slave under its law. He then sued in U.S. federal court, which ruled against him by deciding that it had to employ Missouri police force to the example. He and so appealed to the U.Due south. Supreme Court.

In March 1857, the Supreme Courtroom issued a vii–two decision confronting Scott. In an opinion written by Chief Justice Roger Taney, the Court ruled that people of African descent "are non included, and were not intended to exist included, under the word 'citizens' in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States". Taney supported his ruling with an extended survey of American country and local laws from the time of the Constitution's drafting in 1787 that purported to testify that a "perpetual and impassable bulwark was intended to be erected between the white race and the one which they had reduced to slavery". Considering the Courtroom ruled that Scott was not an American citizen, he was likewise not a denizen of whatever state and, appropriately, could never establish the "diversity of citizenship" that Article III of the U.Southward. Constitution requires for a U.Southward. federal court to be able to practice jurisdiction over a case.[iii] Later on ruling on those issues surrounding Scott, Taney continued further and struck downward the entire Missouri Compromise as a limitation on slavery that exceeded the U.S. Congress'southward constitutional powers.

Although Taney and several other justices hoped the conclusion would permanently settle the slavery controversy, which was increasingly dividing the American public, the decision's effect was the opposite.[9] Taney'due south majority opinion suited the slaveholding states, but was intensely decried in all the other states.[4] The decision inflamed the national fence over slavery and deepened the carve up that led ultimately to the American Civil War. In 1865, after the Union's victory, the Courtroom's ruling in Dred Scott was superseded by the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which abolished slavery, and the Fourteenth Amendment, whose beginning section guaranteed citizenship for "all persons born or naturalized in the Us, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof".

Groundwork [edit]

Political setting [edit]

The Missouri Compromise created the slave-holding state Missouri (Mo., yellow) merely prohibited slavery in the rest of the former Louisiana Territory (here, marked Missouri Territory 1812, green) north of the 36°30' Due north parallel.

In the late 1810s, a major political dispute arose over the creation of new American states from the vast territory the United States had acquired from French republic in 1803 through the Louisiana Purchase.[x] The dispute centered on whether the new states would be "complimentary" states, like the Northern states, in which slavery would be illegal, or whether they would be "slave" states, similar the Southern states, in which slavery would be legal.[10] The Southern states wanted the new states to be slave states in order to raise their own political and economic power. The Northern states wanted the new states to be free states for their own political and economic reasons, as well as their moral concerns over allowing the institution of slavery to expand.

In 1820, the U.S. Congress passed legislation known as the "Missouri Compromise" that was intended to resolve the dispute. The Compromise kickoff admitted Maine into the Marriage as a complimentary state, and then created Missouri out of a portion of the Louisiana Buy territory and admitted it every bit a slave state; at the same time it prohibited slavery in the expanse north of the Parallel 36°30′ north, where almost of the territory lay.[10] The legal effects of a slaveowner taking his slaves from Missouri into the costless territory northward of the 36°30′ n parallel, also every bit the constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise itself, eventually came to a head in the Dred Scott case.

Dred Scott and John Emerson [edit]

Dred Scott was born a slave in Virginia effectually 1799.[eleven] Footling is known of his early on years.[12] His owner, Peter Blow, moved to Alabama in 1818, taking his half-dozen slaves forth to work a farm most Huntsville. In 1830, Accident gave up farming and settled in St. Louis, Missouri, where he sold Scott to U.S. Regular army surgeon Dr. John Emerson.[xiii] Later on purchasing Scott, Emerson took him to Fort Armstrong in Illinois. A free state, Illinois had been free as a territory under the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, and had prohibited slavery in its constitution in 1819 when information technology was admitted equally a state.

In 1836, Emerson moved with Scott from Illinois to Fort Snelling in the Wisconsin territory in what has become the state of Minnesota. Slavery in the Wisconsin Territory (some of which, including Fort Snelling, was part of the Louisiana Buy) was prohibited by the U.S. Congress nether the Missouri Compromise. During his stay at Fort Snelling, Scott married Harriet Robinson in a civil ceremony by Harriet'due south owner, Major Lawrence Taliaferro, a justice of the peace who was also an Indian agent. The anniversary would have been unnecessary had Dred Scott been a slave, as slave marriages had no recognition in the police force.[14] [13]

In 1837, the ground forces ordered Emerson to Jefferson Barracks War machine Mail, southward of St. Louis. Emerson left Scott and his wife at Fort Snelling, where he leased their services out for profit. Past hiring Scott out in a free state, Emerson was finer bringing the institution of slavery into a gratis land, which was a direct violation of the Missouri Compromise, the Northwest Ordinance, and the Wisconsin Enabling Act.[14]

Irene Sanford Emerson [edit]

Before the end of the yr, the army reassigned Emerson to Fort Jesup in Louisiana, where Emerson married Eliza Irene Sanford in February 1838. Emerson sent for Scott and Harriet, who proceeded to Louisiana to serve their principal and his wife. Within months, Emerson was transferred back to Fort Snelling. While en road to Fort Snelling, Scott's girl Eliza was born on a steamboat nether way on the Mississippi River between Illinois and what would become Iowa. Because Eliza was born in costless territory, she was technically built-in as a free person nether both federal and state laws. Upon entering Louisiana, the Scotts could have sued for their freedom, but did not. One scholar suggests that, in all likelihood, the Scotts would take been granted their freedom past a Louisiana court, as it had respected laws of free states that slaveholders forfeited their right to slaves if they brought them in for extended periods. This had been the holding in Louisiana state courts for more than xx years.[fourteen]

Toward the end of 1838, the army reassigned Emerson back to Fort Snelling. By 1840, Emerson'south wife Irene returned to St. Louis with their slaves, while Dr. Emerson served in the Seminole State of war. While in St. Louis, she hired them out. In 1842, Emerson left the regular army. After he died in the Iowa Territory in 1843, his widow Irene inherited his estate, including the Scotts. For three years subsequently John Emerson'south death, she continued to lease out the Scotts as hired slaves. In 1846, Scott attempted to purchase his and his family's freedom, but Irene Emerson refused, prompting Scott to resort to legal recourse.[fifteen]

Procedural history [edit]

Scott v. Emerson [edit]

Starting time state circuit court trial [edit]

Having been unsuccessful in his attempt to purchase his freedom, Dred Scott, with the help of his legal advisers, sued Emerson for his freedom in the Circuit Court of St. Louis County on Apr half dozen, 1846.[16] : 36 A divide petition was filed for his married woman Harriet, making them the first married couple to file liberty suits in tandem in its fifty-year history.[17] : 232 They received financial help from the family of Dred's previous owner, Peter Blow.[14] Blow's daughter Charlotte was married to Joseph Charless, an officeholder at the Bank of Missouri. Charless signed legal documents as security for the Scotts and later secured the services of the bank'southward attorney, Samuel Mansfield Bay, for the trial.[13]

It was expected that the Scotts would win their liberty with relative ease.[14] [17] : 241 By 1846, dozens of freedom suits had been won in Missouri by quondam slaves.[17] Most had claimed their legal right to freedom on the basis that they, or their mothers, had previously lived in free states or territories.[17] Among the most of import legal precedents were Winny 5. Whitesides [xviii] and Rachel v. Walker. [19] In Winny 5. Whitesides, the Missouri Supreme Courtroom had ruled in 1824 that a person who had been held every bit a slave in Illinois, where slavery was illegal, and then brought to Missouri, was free by virtue of residence in a free state.[16] : 41 In Rachel 5. Walker, the land supreme court had ruled that a U.S. Army officer who took a slave to a armed forces mail service in a territory where slavery was prohibited and retained her in that location for several years, had thereby "forfeit[ed] his holding".[16] : 42 Rachel, similar Dred Scott, had accompanied her enslaver to Fort Snelling.[16]

Scott was represented past three dissimilar lawyers from the filing of the original petition to the time of the bodily trial, over one twelvemonth later. The first was Francis B. Murdoch, a prolific liberty suit attorney who abruptly left St. Louis.[20] [16] : 38 Murdoch was replaced by Charles D. Drake, an in-police of the Blow family.[16] When Drake too left the state, Samuel Chiliad. Bay took over every bit the Scotts' lawyer.[sixteen] Irene Emerson was represented by George W. Goode, a proslavery lawyer from Virginia.[21] : 130 By the time the example went to trial, it had been reassigned from Guess John M. Krum, who was proslavery, to Approximate Alexander Hamilton, who was known to exist sympathetic to freedom suits.[xiii]

Dred Scott v. Irene Emerson finally went to trial for the first time on June xxx, 1847.[21] : 130 Henry Peter Blow testified in courtroom that his male parent had owned Dred and sold him to John Emerson.[16] : 44 The fact that Scott had been taken to alive on free soil was clearly established through depositions from witnesses who had known Scott and Dr. Emerson at Fort Armstrong and Fort Snelling.[21] : 130–131 Grocer Samuel Russell testified that he had hired the Scotts from Irene Emerson and paid her father, Alexander Sanford, for their services.[21] Upon cross test, however, Russell admitted that the leasing arrangements had actually been made by his wife, Adeline.[21]

Thus, Russell's testimony was ruled hearsay, and the jury returned a verdict for Emerson.[13] This created a seemingly contradictory result in which Scott was ordered by the court to remain Irene Emerson'southward slave, because he had been unable to show that he was previously Irene Emerson's slave.[thirteen]

Kickoff country supreme courtroom appeal [edit]

Bay moved immediately for a new trial on the basis that Scott's case had been lost due to a technicality which could exist rectified, rather than the facts.[16] : 47 Judge Hamilton finally issued the order for a new trial on December ii, 1847.[xvi] Two days afterwards, Emerson's lawyer objected to a new trial by filing a bill of exceptions.[16] [21] : 131 The case was then taken on writ of mistake to the Supreme Courtroom of Missouri.[13] Scott's new lawyers, Alexander P. Field and David N. Hall, argued that the writ of mistake was inappropriate because the lower court had not yet issued a final judgment.[16] : 50 The country supreme court agreed unanimously with their position and dismissed Emerson'due south appeal on June 30, 1848.[16] The main upshot before the court at this stage was procedural and no substantive bug were discussed.[sixteen]

Second state circuit court trial [edit]

Before the land supreme court had convened, Goode had presented a motility on behalf of Emerson to have Scott taken into custody and hired out.[21] On March 17, 1848, Judge Hamilton issued the order to the St. Louis County sheriff.[16] [b] Anyone hiring Scott had to postal service a bail of six-hundred dollars.[sixteen] : 49 Wages he earned during that time were placed in escrow, to be paid to the party that prevailed in the lawsuit.[16] Scott would remain in the sheriff's custody or hired out past him until March 18, 1857.[xvi] 1 of Scott's lawyers, David N. Hall, hired him starting March 17, 1849.[17] : 261

The St. Louis Fire of 1849, a cholera epidemic, and two continuances delayed the retrial in the St. Louis Circuit Court until January 12, 1850.[13] [sixteen] : 51 Irene Emerson was now defended past Hugh A. Garland and Lyman D. Norris, while Scott was represented by Field and Hall.[16] Guess Alexander Hamilton was presiding.[13] The proceedings were similar to the offset trial.[16] : 52 The same depositions from Catherine A. Anderson and Miles H. Clark were used to constitute that Dr. Emerson had taken Scott to free territory.[sixteen]

This time, the hearsay problem was surmounted by a deposition from Adeline Russell stating that she had hired the Scotts from Irene Emerson, thereby proving that Emerson claimed them as her slaves.[16] Samuel Russell testified in court one time again that he had paid for their services.[sixteen] The defense so changed strategy and argued in their summation that Mrs. Emerson had every right to hire out Dred Scott, because he had lived with Dr. Emerson at Fort Armstrong and Fort Snelling under military jurisdiction, not under civil law.[16] [21] : 132 In doing so, the defense force ignored the precedent set past Rachel v. Walker. [21] In his rebuttal, Hall stated that the fact that they were military posts did not matter, and pointed out that Dr. Emerson had left Scott behind at Fort Snelling, hired out to others, afterwards being reassigned to a new post.[22]

The jury quickly returned a verdict in favor of Dred Scott, nominally making him a free man.[21] [16] : 53 Judge Hamilton alleged Harriet, Eliza and Lizzie Scott to be complimentary as well.[16] Garland moved immediately for a new trial, and was overruled.[22] [16] : 55 On February xiii, 1850, Emerson's defence filed a bill of exceptions, which was certified past Judge Hamilton, setting into movement another appeal to the Missouri Supreme Court.[sixteen] Counsel for the opposing sides signed an understanding that moving forward, only Dred Scott v. Irene Emerson would be advanced, and that whatever decision fabricated past the high court would employ to Harriet's suit, likewise.[16] : 43 In 1849 or 1850, Irene Emerson left St. Louis and moved to Springfield, Massachusetts.[16] : 55 Her blood brother, John F. A. Sanford, continued looking after her business interests when she left,[23] and her departure had no bear upon on the instance.[16] : 56

Second state supreme court entreatment [edit]

Both parties filed briefs with the Supreme Court of Missouri on March 8, 1850.[sixteen] : 57 A busy docket delayed consideration of the case until the October term.[21] : 133 By then, the outcome of slavery had become politically charged, even within the judiciary.[24] [21] : 134 Although the Missouri Supreme Court had non nevertheless overturned precedent in liberty suits, in the 1840s, the courtroom's proslavery justices had explicitly stated their opposition to freeing slaves.[24] After the court convened on October 25, 1850, the two justices who were proslavery anti-Benton Democrats – William Barclay Napton and James Harvey Birch – persuaded John Ferguson Ryland, a Benton Democrat, to join them in a unanimous decision that Dred Scott remained a slave under Missouri constabulary.[21] [xvi] : 60 Notwithstanding, Gauge Napton delayed writing the court'due south stance for months.[21] Then in August 1851, both Napton and Birch lost their seats in the Missouri Supreme Court, following the state's first supreme court ballot, with merely Ryland remaining as an incumbent.[21] The instance thus needed to be considered again past the newly elected courtroom.[21] : 135 The reorganized Missouri Supreme Courtroom at present included 2 "moderates" – Hamilton Gamble and John Ryland – and one staunch proslavery justice, William Scott.[24]

David North. Hall had prepared the brief for Dred Scott, but died in March 1851.[16] : 57, 61 Alexander P. Field connected alone as counsel for Dred Scott, and resubmitted the same briefs from 1850 for both sides.[16] On Nov 29, 1851, the instance was taken under consideration, on written briefs alone, and a decision was reached.[16] However, before Judge Scott could write the court's opinion, Lyman Norris, co-counsel for Irene Emerson, obtained permission to submit a new brief he had been preparing, to supplant the original ane submitted by Garland.[xvi] : 56,61

Norris'southward brief has been characterized as "a sweeping denunciation of the authority of both the [Northwest] Ordinance of 1787 and the Missouri Compromise."[16] : 62 Although he stopped short of questioning their constitutionality, Norris questioned their applicability and criticized the early on Missouri Supreme Court, ridiculing former Justice George Tompkins as "the great apostle of freedom at that solar day."[24] [16] Reviewing the court'south past decisions on freedom suits, Norris acknowledged that if Rachel v. Walker was immune to stand, his customer would lose.[24] Norris and then challenged the concept of "once free, always costless", and asserted that the court under Tompkins had been wrong to dominion that the Ordinance of 1787 remained in force afterwards the ratification of the U.S. Constitution in 1788.[24] Finally, he argued that the Missouri Compromise should be disregarded whenever it interfered with Missouri police, and that the laws of other states should not be enforced, if their enforcement would cause Missouri citizens to lose their property.[24] In support of his statement, he cited Master Justice Roger B. Taney'southward opinion in the United states Supreme Courtroom case Strader v. Graham, which argued that the status of a slave returning from a free country must be determined by the slave country itself.[24] [16] : 63 According to historian Walter Ehrlich, the closing of Norris's brief was "a racist harangue that not only revealed the prejudices of its author, just also indicated how the Dred Scott case had go a vehicle for the expression of such views".[16] : 63 Noting that Norris'south proslavery "doctrines" were later incorporated into the court's final decision,[16] : 62 Ehrlich writes (accent his):

From this point on, the Dred Scott case clearly changed from a genuine freedom arrange to the controversial political consequence for which it became infamous in American history. [16]

On March 22, 1852, Approximate William Scott announced the decision of the Missouri Supreme Court that Dred Scott remained a slave, and ordered the trial court's judgment to be reversed.[21] : 137 Guess Ryland concurred, while Chief Justice Hamilton Take a chance dissented.[24] The majority opinion written by Judge Scott focused on the event of comity or conflict of laws,[21] and relied on "states' rights" rhetoric:[16] : 65

Every Land has the right of determining how far, in a spirit of comity, it volition respect the laws of other States. Those laws have no intrinsic right to exist enforced across the limits of the State for which they were enacted. The respect immune them will depend birthday on their conformity to the policy of our institutions. No State is bound to carry into effect enactments conceived in a spirit hostile to that which pervades her own laws.[25]

Judge Scott did not deny the constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise, and acknowledged that its prohibition of slavery was "absolute", merely only inside the specified territory.[16] Thus, a slave crossing the border could obtain his liberty, but merely within the court of the free state.[sixteen] Rejecting the court'southward own precedent, Scott argued that "'Once free' did not necessarily mean 'always free.'"[16] : 66 He cited the Kentucky Court of Appeals decision in Graham v. Strader, which had held that a Kentucky slaveowner who permitted a slave to go to Ohio temporarily, did not forfeit ownership of the slave.[xvi] To justify overturning 3 decades of precedent, Judge Scott argued that circumstances had inverse:[21]

Times now are non as they were when the erstwhile decisions on this subject field were made. Since and then not only individuals simply States have been possessed with a dark and fell spirit in relation to slavery, whose gratification is sought in the pursuit of measures, whose inevitable event must exist the overthrow and devastation of our government. Nether such circumstances it does non behoove the State of Missouri to bear witness the least eyebrow to any measure which might gratify this spirit. She is willing to assume her full responsibility for the existence of slavery within her limits, nor does she seek to share or divide information technology with others.[25]

On March 23, 1852, the day after the Missouri Supreme Courtroom decision had been announced, Irene Emerson'south lawyers filed an order in the St. Louis Circuit Court for the bonds signed by the Blow family to cover the Scotts' court costs; return of the slaves themselves; and transfer of their wages earned over iv years, plus 6 percent interest.[13] On June 29, 1852, Estimate Hamilton overruled the order.[sixteen] : seventy

Scott five. Sanford [edit]

The instance looked hopeless, and the Accident family unit could no longer pay for Scott'southward legal costs. Scott likewise lost both of his lawyers when Alexander Field moved to Louisiana and David Hall died. The case was undertaken pro bono by Roswell Field, who employed Scott as a janitor. Field also discussed the example with LaBeaume, who had taken over the lease on the Scotts in 1851.[26] Later the Missouri Supreme Courtroom determination, Guess Hamilton turned down a request by Emerson's lawyers to release the rent payments from escrow and to evangelize the slaves into their possessor's custody.[xiii]

In 1853, Dred Scott over again sued his current owner John Sanford, but this fourth dimension in federal court. Sanford returned to New York and the federal courts had multifariousness jurisdiction under Article Iii, Department 2 of the U.S. Constitution. In addition to the existing complaints, Scott declared that Sanford had assaulted his family and held them captive for six hours on January 1, 1853.[27]

At trial in 1854, Judge Robert William Wells directed the jury to rely on Missouri law on the question of Scott's freedom. Since the Missouri Supreme Court had held that Scott remained a slave, the jury found in favor of Sanford. Scott then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Courtroom, where the clerk misspelled the defendant's proper name, and the case was recorded as Dred Scott v. Sandford, with an ever-erroneous title. Scott was represented before the Supreme Court past Montgomery Blair and George Ticknor Curtis, whose blood brother Benjamin was a Supreme Courtroom Justice. Sanford was represented by Reverdy Johnson and Henry S. Geyer.[xiii]

Sanford as defendant [edit]

When the instance was filed, the ii sides agreed on a statement of facts that claimed Scott had been sold by Dr. Emerson to John Sanford, though this was a legal fiction. Dr. Emerson had died in 1843, and Dred Scott had filed his 1847 adjust against Irene Emerson. There is no record of Dred Scott's transfer to Sanford or of his transfer dorsum to Irene. John Sanford died shortly earlier Scott'due south manumission, and Scott was non listed in the probate records of Sanford's manor.[26] Also, Sanford was not acting as Dr. Emerson'southward executor, every bit he was never appointed by a probate court, and the Emerson estate had been settled when the federal case was filed.[fourteen]

The murky circumstances of ownership led many to conclude the parties to Dred Scott v. Sandford contrived to create a test example.[15] [26] [27] Mrs. Emerson's remarriage to abolitionist U.South. Representative Calvin C. Chaffee seemed suspicious to contemporaries, and Sanford was thought to be a front and to have allowed himself to be sued, despite not really being Scott's owner. Nevertheless, Sanford had been involved in the case since 1847, before his sister married Chaffee. He had secured counsel for his sister in the state case, and he engaged the same lawyer for his own defense force in the federal case.[15] Sanford too consented to be represented past 18-carat pro-slavery advocates earlier the Supreme Court, rather than to put upwardly a token defence.

Influence of President Buchanan [edit]

Historians discovered that after the Supreme Court heard arguments in the instance but before information technology issued a ruling, President-elect James Buchanan wrote to his friend, Supreme Court Associate Justice John Catron, to ask whether the case would be decided by the Court before his inauguration in March 1857.[28] Buchanan hoped that the conclusion would quell unrest in the state over the slavery issue past issuing a ruling to have it out of political argue. He afterwards successfully pressured Associate Justice Robert Cooper Grier, a Northerner, to join the Southern bulk in Dred Scott to prevent the appearance that the decision was made along sectional lines.[29]

Biographer Jean H. Bakery articulates the view that Buchanan'south use of political pressure on a member of a sitting court was regarded then, as now, to be highly improper.[30] Republicans fueled speculation every bit to Buchanan's influence by publicizing that Taney had secretly informed Buchanan of the conclusion. Buchanan alleged in his inaugural address that the slavery question would "be speedily and finally settled" by the Supreme Courtroom.[31] [14]

Supreme Court determination [edit]

On March 6, 1857, the U.Due south. Supreme Court ruled against Dred Scott in a vii–2 decision that fills over 200 pages in the United states Reports.[10] The decision contains opinions from all nine justices, but the "majority opinion" has e'er been the focus of the controversy.[32]

Opinion of the Court [edit]

Seven justices formed the bulk and joined an stance written by chief justice Roger Taney. Taney began with what he saw every bit the core issue in the example: whether or not black people could possess federal citizenship under the U.S. Constitution.[ten]

The question is simply this: Can a negro, whose ancestors were imported into this land, and sold as slaves, become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States, and equally such become entitled to all of the rights, and privileges, and immunities, guarantied [sic] by that instrument to the citizen?

— Dred Scott, 60 U.S. at 403.

In answer, the Court ruled that they could not. It held that black people could non exist American citizens, and therefore a lawsuit to which they were a political party could never qualify for the "diverseness of citizenship" that Commodity III of the Constitution requires for American federal courts to have jurisdiction over cases that do not involve federal questions.[10]

The chief rationale for the Courtroom'southward ruling was Taney's assertion that blackness African slaves and their descendants were never intended to be part of the American social and political landscape.[10]

We think ... that [black people] are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word "citizens" in the Constitution, and tin can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that musical instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the Usa. On the contrary, they were at that time [of America's founding] considered as a subordinate and junior form of beings who had been subjugated past the ascendant race, and, whether emancipated or not, nonetheless remained subject area to their potency, and had no rights or privileges only such every bit those who held the power and the Government might choose to grant them.

— Dred Scott, threescore U.S. at 404–05.[33]

Taney then extensively reviewed laws from the original American states that involved the status of black Americans at the time of the Constitution'southward drafting in 1787.[ten] He concluded that these laws showed that a "perpetual and impassable bulwark was intended to exist erected between the white race and the ane which they had reduced to slavery".[34] Thus, he concluded, black people were non American citizens, and could not sue as citizens in federal courts.[10] This meant that U.Southward. states lacked the power to alter the legal condition of blackness people by granting them state citizenship.[32]

It is difficult at this day to realize the state of public opinion in relation to that unfortunate race, which prevailed in the civilized and enlightened portions of the world at the time of the Proclamation of Independence, and when the Constitution of the United States was framed and adopted. ... They had for more than than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order ... and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white human was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit.

— Dred Scott, 60 U.Due south. at 407.

This holding unremarkably would have concluded the decision, since it tending of Dred Scott's case, but Taney did not conclude the matter before the Courtroom in the normal manner.[ten] He went on to appraise the constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise itself, writing that the Compromise'due south legal provisions intended to free slaves who were living due north of the 36°Due north latitude line in the western territories. In the Court's judgment, this would plant the government depriving slaveowners of their property—since slaves were legally the property of their owners—without due process of law, which is forbidden under the Fifth Subpoena to the Constitution.[35] Taney as well reasoned that the Constitution and the Pecker of Rights implicitly precluded any possibility of ramble rights for blackness African slaves and their descendants.[32] Thus, Taney concluded:

Now, ... the right of property in a slave is distinctly and expressly affirmed in the Constitution. ... Upon these considerations, it is the opinion of the court that the deed of Congress which prohibited a citizen from holding and owning holding of this kind in the territory of the United States northward of the [36°N 36' latitude] line therein mentioned, is not warranted by the Constitution, and is therefore void.

— Dred Scott, 60 U.S. at 451–52.

Taney held that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional, marking the commencement fourth dimension since the 1803 example Marbury v. Madison that the Supreme Court had struck downwards a federal law, although the Missouri Compromise had already been effectively overridden past the Kansas–Nebraska Act. Taney made this argument on a narrow definition of the Property Clause of Section 3 of Article 4 of the Constitution. The Property Clause states, "The Congress shall have Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Belongings belonging to the Us..." Taney made the argument that the Property Clause "applied only to the property which the States held in mutual at that fourth dimension, and has no reference whatever to any territory or other property which the new sovereignty might afterwards itself acquire."[36] Taney asserted that because the Northwest Territory was not part of the U.s.a. at the time of the Constitution's ratification, Congress did not have the dominance to ban slavery in the territory. Co-ordinate to Taney, the Missouri Compromise exceeded the scope of Congress's powers and was unconstitutional, and thus Dred Scott was all the same a slave regardless of his time spent in the parts of the Northwest Territory that were north of 36°N,[37] and he was yet a slave under Missouri law, and the Court had to follow Missouri law in the matter. For all these reasons, the Court concluded that Scott could not bring suit in U.S. federal court.[37]

Dissents [edit]

Justices Benjamin Robbins Curtis and John McLean were the but ii dissenters from the Court's conclusion, and both filed dissenting opinions.

Curtis's 67-folio dissent argued that Taney'south assertion that black people could not possess federal U.S. citizenship was historically and legally baseless.[32] Curtis pointed out that at the fourth dimension of the Constitution's adoption in 1789, blackness men could vote in five of the xiii states. Legally, that made them citizens of both their individual states and the United States federally. Curtis cited many country statutes and state court decisions supporting his position. His dissent was "extremely persuasive", and it prompted Taney to add eighteen additional pages to his stance in an try to rebut Curtis's arguments.[32]

McLean's dissent deemed the statement that black people could not be citizens "more than a affair of gustatory modality than of law". He attacked much of the Court's conclusion as obiter dicta that was not legally administrative on the basis that one time the court adamant that it did not have jurisdiction to hear Scott'due south case, information technology should accept simply dismissed the action, rather than passing judgment on the merits of the claims.

Curtis and McLean both attacked the Court's overturning of the Missouri Compromise on its merits. They noted that it was not necessary to decide the question and that none of the authors of the Constitution had ever objected on constitutional grounds to the Congress's adoption of the antislavery provisions of the Northwest Ordinance passed by the Continental Congress or the subsequent acts that barred slavery north of 36°30' N, or the prohibition on importing slaves from overseas passed in 1808. Curtis said slavery was not listed in the constitution as a "natural right", merely rather a creation of municipal law. He pointed out the constitution said "The Congress shall have Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Belongings belonging to the United States; and nothing in this Constitution shall be so construed every bit to Prejudice any Claims of the United States, or of any detail State." Since slavery was not mentioned as an exception, he felt a prohibition of it fell within the scope of needed rules and regulations Congress was gratuitous to pass.[38]

Reactions [edit]

The Supreme Courtroom's conclusion in Dred Scott was "greeted with unmitigated wrath from every segment of the United States except the slave holding states."[32] The American political historian Robert Thou. McCloskey described:

The tempest of malediction that burst over the judges seems to have stunned them; far from extinguishing the slavery controversy, they had fanned its flames and had, moreover, deeply endangered the security of the judicial arm of government. No such vilification every bit this had been heard even in the wrathful days following the Alien and Sedition Acts. Taney's opinion was assailed by the Northern printing equally a wicked "stump speech" and was shamefully misquoted and distorted. "If the people obey this conclusion," said i paper, "they disobey God."[37]

Many Republicans, including Abraham Lincoln, who was rapidly becoming the leading Republican in Illinois, regarded the decision equally part of a plot to expand and eventually impose the legalization of slavery throughout all of u.s..[39] Some southern extremists wanted all states to recognize slavery as a ramble right. Lincoln rejected the court'due south bulk opinion that "the correct of belongings in a slave is distinctly and expressly affirmed in the Constitution," pointing out that the constitution did not ever mention property in reference to slaves and in fact explicitly referred to them every bit "persons".[40] Southern Democrats considered Republicans to be lawless rebels who were provoking disunion by their refusal to accept the Supreme Courtroom'south decision as the law of the land. Many northern opponents of slavery offered a legal argument for refusing to recognize the Dred Scott decision on the Missouri Compromise equally binding. They argued that the Court'southward determination that the federal courts had no jurisdiction to hear the case rendered the remainder of the decision obiter dictum—a non binding passing remark rather than an authoritative interpretation of the police. Douglas attacked that position in the Lincoln-Douglas debates:

Mr. Lincoln goes for a warfare upon the Supreme Courtroom of the Us, because of their judicial conclusion in the Dred Scott case. I yield obedience to the decisions in that courtroom—to the final determination of the highest judicial tribunal known to our constitution.

In a speech at Springfield, Illinois, Lincoln responded that the Republican Political party was non seeking to defy the Supreme Court, merely he hoped they could convince it to reverse its ruling.[41]

Nosotros believe, as much as Guess Douglas, (perhaps more than) in obedience to, and respect for the judicial section of government. We call back its decisions on Ramble questions, when fully settled, should control, not only the particular cases decided, only the general policy of the land, subject area to be disturbed only by subpoena of the Constitution every bit provided in that instrument itself. More this would be revolution. But we think the Dred Scott decision is erroneous. Nosotros know the court that made it, has ofttimes over-ruled its own decisions, and nosotros shall do what nosotros can to have information technology to over-dominion this. We offer no resistance to it.

Democrats had refused to take the courtroom's estimation of the U.S. Constitution as permanently binding. During the Andrew Jackson administration, Taney, and then Attorney General, had written:

Any may be the forcefulness of the decision of the Supreme Court in binding the parties and settling their rights in the particular example before them, I am not prepared to acknowledge that a construction given to the constitution by the Supreme Court in deciding any one or more than cases fixes of itself irrevokably [sic] and permanently its construction in that particular and binds the states and the Legislative and executive branches of the General government, forever after to adapt to it and adopt it in every other case equally the truthful reading of the instrument although all of them may unite in believing information technology erroneous.[42]

Frederick Douglass, a prominent blackness abolitionist who considered the decision to be unconstitutional and Taney's reasoning opposite to the Founding Fathers' vision, predicted that political conflict could not be avoided:

The highest dominance has spoken. The voice of the Supreme Court has gone out over the troubled waves of the National Conscience.... [Just] my hopes were never brighter than at present. I have no fear that the National Conscience volition be put to slumber by such an open, glaring, and scandalous tissue of lies....[43]

Co-ordinate to Jefferson Davis, then a U.S. Senator from Mississippi, and future President of the Confederate States of America, the case merely "presented the question whether Cuffee [a derogatory term for a black person] should be kept in his normal condition or not . . . [and] whether the Congress of the United States could make up one's mind what might or might not be holding in a Territory–the case being that of an officer of the regular army sent into a Territory to perform his public duty, having taken with him his negro slave".[44]

Impact on both parties [edit]

Irene Emerson moved to Massachusetts in 1850 and married Calvin C. Chaffee, a doctor and abolitionist who was elected to Congress on the Know Nothing and Republican tickets. Following the Supreme Court ruling, pro-slavery newspapers attacked Chaffee equally a hypocrite. Chaffee protested that Dred Scott belonged to his brother-in-police and that he had goose egg to do with Scott's enslavement.[27] Nevertheless, the Chaffees executed a deed transferring the Scott family to Henry Taylor Accident, the son of Scott's former owner, Peter Blow. Chaffee'south lawyer suggested the transfer as the most convenient way of freeing Scott since Missouri law required manumitters to appear in person before the court.[27]

Taylor Blow filed the manumission papers with Gauge Hamilton on May 26, 1857. The emancipation of Dred Scott and his family unit was national news and was celebrated in northern cities. Scott worked as a porter in a hotel in St. Louis, where he was a minor celebrity. His married woman took in laundry. Dred Scott died of tuberculosis on November 7, 1858. Harriet died on June 17, 1876.[thirteen]

Aftermath [edit]

Economic [edit]

Economist Charles Calomiris and historian Larry Schweikart discovered that uncertainty virtually whether the entire West would suddenly become slave territory or engulfed in combat similar "Bleeding Kansas" gripped the markets immediately. The e–west railroads complanate immediately (although due north–south lines were unaffected), causing, in turn, the near-collapse of several large banks and the runs that ensued. What followed the runs has been called the Panic of 1857.

The Panic of 1857, unlike the Panic of 1837, nearly exclusively impacted the North, a fact that Calomiris and Schweikart aspect to the South's system of branch banking, as opposed to the N'south system of unit banking. In the Southward's co-operative banking arrangement, data moved reliably among the branch banks and manual of the panic was minor. Northern unit banks, in dissimilarity, were competitors and seldom shared such vital information.[45]

Political [edit]

Southerners, who had grown uncomfortable with the Kansas-Nebraska Act, argued that they had a constitutional correct to bring slaves into the territories, regardless of any decision by a territorial legislature on the subject. The Dred Scott determination seemed to endorse that view.

Although Taney believed that the decision represented a compromise that would exist a final settlement of the slavery question past transforming a contested political issue into a affair of settled police force, the decision produced the reverse result. Information technology strengthened Northern opposition to slavery, divided the Autonomous Party on sectional lines, encouraged secessionist elements amidst Southern supporters of slavery to make bolder demands, and strengthened the Republican Party.

After references [edit]

In 1859, when defending John Anthony Copeland and Shields Green from the charge of treason, following their participation in John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, their chaser, George Sennott, cited the Dred Scott decision in arguing successfully that since they were not citizens co-ordinate to that Supreme Court ruling, they could not commit treason.[46] The charge of treason was dropped, but they were found guilty and executed on other charges.

Justice John Marshall Harlan was the lonely dissenting vote in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which declared racial segregation constitutional and created the concept of "split up just equal". In his dissent, Harlan wrote that the majority's opinion would "prove to be quite as pernicious as the decision fabricated by this tribunal in the Dred Scott example".[47]

Charles Evans Hughes, writing in 1927 on the Supreme Courtroom's history, described Dred Scott v. Sandford equally a "cocky-inflicted wound" from which the court would not recover for many years.[48] [49] [50]

In a memo to Justice Robert H. Jackson in 1952, for whom he was clerking, on the subject of Brown 5. Lath of Instruction, the time to come Principal Justice William H. Rehnquist wrote that "Scott v. Sandford was the consequence of Taney's endeavor to protect slaveholders from legislative interference."[51]

Justice Antonin Scalia made the comparison between Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992) and Dred Scott in an effort to see Roe v. Wade overturned:

Dred Scott ... rested upon the concept of "substantive due process" that the Courtroom praises and employs today. Indeed, Dred Scott was very possibly the first awarding of substantive due procedure in the Supreme Court, the original precedent for... Roe five. Wade.[52]

Scalia noted that the Dred Scott decision had been written and championed past Taney and left the justice'southward reputation irrevocably tarnished. Taney, who was attempting to end the disruptive question of the future of slavery, wrote a decision that "inflamed the national debate over slavery and deepened the separate that led ultimately to the American Civil War".[53]

Master Justice John Roberts compared Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) to Dred Scott, every bit another example of trying to settle a contentious upshot through a ruling that went across the scope of the Constitution.[54]

Legacy [edit]

- 1977: The Scotts' smashing-grandson, John A. Madison, Jr., an attorney, gave the invocation at the ceremony at the Old Courthouse in St. Louis, a National Historic Landmark, for the dedication of a National Celebrated Mark commemorating the Scotts' case tried in that location.[55]

- 2000: Harriet and Dred Scott's petition papers in their freedom accommodate were displayed at the main branch of the St. Louis Public Library, following the discovery of more than 300 freedom suits in the archives of the U.Due south. circuit court.[56]

- 2006: A new celebrated plaque was erected at the Old Courthouse to honor the active roles of both Dred and Harriet Scott in their freedom suit and the case'south significance in U.S. history.[57]

- 2012: A monument depicting Dred and Harriet Scott was erected at the One-time Courthouse's east entrance facing the St. Louis Gateway Arch.[58]

See likewise [edit]

- Anticanon

- American slave court cases

- Freedom adapt

- Origins of the American Ceremonious War

- Privileges and Immunities Clause

- Timeline of the civil rights motion

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b John Sandford'south surname was actually "Sanford". A Supreme Court clerk of courtroom misspelled his name in 1856 and the error was never corrected.[1]

- ^ Legal historian Walter Ehrlich implies that the custody order practical only to Dred Scott, while Don Fehrenbacher suggests that it applied to both Dred and Harriet.

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ Vishneski (1988), p. 373, note 1.

- ^ Daniel A. Farber, A Fatal Loss of Balance: Dred Scott Revisited, UC Berkeley Public Police Research Paper No. 1782963 (2011).

- ^ a b Chemerinsky (2015), p. 722. sfnp error: no target: CITEREFChemerinsky2015 (help)

- ^ a b Nowak & Rotunda (2012), §xviii.half-dozen.

- ^ Staff (October 14, 2015). "13 Worst Supreme Court Decisions of All Fourth dimension". FindLaw . Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ Bernard Schwartz (1997). A Volume of Legal Lists: The Best and Worst in American Law . Oxford University Printing. p. 70. ISBN978-0-xix-802694-five.

- ^ Junius P. Rodriguez (2007). Slavery in the U.s.: A Social, Political, and Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 1. ISBN9781851095445.

- ^ David Konig; et al. (2010). The Dred Scott Case: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Race and Law. Ohio Academy Press. p. 213. ISBN9780821419120.

- ^ Chemerinsky (2015), p. 723. sfnp fault: no target: CITEREFChemerinsky2015 (help)

- ^ a b c d eastward f g h i j Chemerinsky (2019), § nine.3.i, p. 750.

- ^ Melvin I. Urofsky, Dred Scott at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Earl M. Maltz, Dred Scott and the Politics of Slavery (2007)

- ^ a b c d e f yard h i j 1000 l yard "Missouri's Dred Scott Instance, 1846–1857". Missouri Digital Heritage: African American History Initiative . Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c d eastward f thousand Finkelman (2007).

- ^ a b c Don Due east. Fehrenbacher, The Dred Scott Instance: Its Significance in American Police force and Politics (2001)

- ^ a b c d eastward f g h i j k l chiliad n o p q r s t u v west x y z aa ab air-conditioning ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax Ehrlich, Walter (2007). They Have No Rights: Dred Scott'due south Struggle for Liberty. Applewood Books.

- ^ a b c d eastward VanderVelde, Lea (2009). Mrs. Dred Scott: A Life on Slavery's Frontier. Oxford University Printing. ISBN9780195366563.

- ^ one Mo. 472, 475 (Mo. 1824).

- ^ 4 Mo. 350 (Mo. 1836).

- ^ Gardner, Eric (Spring 2007). "'Yous Have No Business to Whip Me': The Freedom Suits of Polly Wash and Lucy Ann Delaney". African American Review. 41 (1): 40, 47. JSTOR 40033764.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m north o p q r s Fehrenbacher, Don Edward (1981). Slavery, Police and Politics: The Dred Scott Case in Historical Perspective. New York: Oxford University Printing. ISBN0-19-502882-ane.

- ^ a b Lawson, John, ed. (1921). American Land Trials. Vol. 13. St. Louis: Thomas Constabulary Book Company. pp. 237–238.

- ^ Finkelman, Paul (Dec 2006). "Scott five. Sandford: The Court'southward Most Dreadful Case and How It Changed History". Chicago-Kent Police force Review. 82 (1): 25 – via Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Boman, Dennis K. (2000). "The Dred Scott Case Reconsidered: The Legal and Political Context in Missouri". American Journal of Legal History. 44 (4): 421, 423–424, 426. doi:10.2307/3113785. JSTOR 3113785.

- ^ a b "Scott v. Emerson, fifteen Mo. 576 (1852)". Caselaw Admission Project, Harvard Law School . Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ a b c Ehrlich, Walter (September 1968). "Was the Dred Scott Instance Valid?". The Periodical of American History. Organization of American Historians. 55 (two): 256–265. doi:10.2307/1899556. JSTOR 1899556.

- ^ a b c d Hardy, David T. (2012). "Dred Scott, John San(d)ford, and the Case for Bunco" (PDF). Northern Kentucky Constabulary Review. 41 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on Oct 10, 2015.

- ^ Maltz, Earl Thou. (2007). Dred Scott and the politics of slavery. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. p. 115. ISBN978-0-7006-1502-5.

- ^ Faragher, John Mack; et al. (2005). Out of Many: A History of the American People (Revised Press (4th Ed) ed.). Englewood Cliffs, North.J: Prentice Hall. p. 388. ISBN0-xiii-195130-0.

- ^ Baker, Jean H. (2004). James Buchanan: The American Presidents Series: The 15th President, 1857–1861. Macmillan. ISBN978-0-8050-6946-four.

- ^ "James Buchanan: Inaugural Address. U.Southward. Countdown Addresses. 1989". Bartleby.com. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Nowak & Rotunda (2012), § 18.6.

- ^ Quoted in part in Chemerinsky (2019), § nine.3.one, p. 750.

- ^ Chemerinsky (2019), § 9.3.one, p. 750, quoting Dred Scott, 60 U.S. at 409.

- ^ Chemerinsky (2019), § nine.three.i, pp. 750–51.

- ^ ( Dred Scott v. Sanford , 60 U.South. 149.)

- ^ a b c McCloskey (2010), p. 62.

- ^ "Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) Excerpts From Majority and Dissenting Opinions". Bill of Rights Found.

- ^ "Digital History". world wide web.digitalhistory.uh.edu . Retrieved June 12, 2019.

- ^ "Abraham Lincoln'southward Cooper Wedlock Address". www.abrahamlincolnonline.org.

- ^ "Speech at Springfield, June 26, 1857".

- ^ Don Eastward. Fehrenbacher (1978/2001), The Dred Scott Example: Its Significance in American Police and Politics, reprint, New York: Oxford, Office three, "Consequences and Echoes", Chapter xviii, "The Judges Judged", p. 441; unpublished opinion, transcript in Carl B. Swisher Papers, Manuscript Partitioning, Library of Congress.

- ^ Finkleman, Paul (March 15, 1997). Dred Scott vs. Sandford: A Brief History with Documents – Google Boeken. ISBN9780312128074.

- ^ Address to the United states of america Senate on May seven, 1860, reprinted equally Appendix F to Davis, Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government (1880).

- ^ Charles Calomiris and Larry Schweikart, "The Panic of 1857: Origins, Transmission, Containment", Periodical of Economic History, LI, December 1990, pp. 807–34.

- ^ Lubet, Steven (June i, 2013). "Execution in Virginia, 1859: The Trials of Green and Copeland". North Carolina Constabulary Review. 91 (5).

- ^ Fehrenbacher, p. 580.

- ^ Hughes, Charles Evans (1936) [1928]. The Supreme Court of the U.s.. Columbia Academy Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN978-0-231-08567-0.

- ^ "Introduction to the court stance on the Dred Scott case". U.S. Section of State. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- ^ "Remarks of the Chief Justice". Supreme Court of the U.s.. March 21, 2003. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ^ Rehnquist, William. "A Random Thought on the Segregation Cases" Archived 2008-09-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey, 505 U.Southward. 833 (1992). FindLaw.

- ^ Carey, Patrick West. (April 2002). "Political Atheism: Dred Scott, Roger Brooke Taney, and Orestes A. Brownson". The Catholic Historical Review. The Cosmic University of America Press. 88 (2): 207–229. doi:10.1353/cat.2002.0072. ISSN 1534-0708. S2CID 153950640.

- ^ Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. (1992).

- ^ Arenson, Adam (2010), "Dred Scott versus the Dred Scott Case", The Dred Scott Case: Historical and Gimmicky Perspectives on Race and Constabulary, Ohio University Press, p. 36, ISBN978-0821419120

- ^ Arenson (2010), p. 38

- ^ Arenson (2010), p. 39

- ^ Patrick, Robert (August xviii, 2015). "St. Louis judges desire sculpture to honor slaves who sought freedom here". stltoday.com . Retrieved September 2, 2018.

Attendees become their showtime look after the unveiling of the new Dred and Harriet Scott statue on the grounds of the Quondam Courthouse in downtown St. Louis on Friday, June 8, 2012.

Works cited [edit]

- Arenson, Adam (2010). "Dred Scott Versus the Dred Scott Case". In Konig, David Thomas; Finkelman, Paul; Bracey, Christopher Alan (eds.). The Dred Scott Instance: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Race and Law. Columbus, OH: Ohio Land Academy Press. ISBN978-0821419120.

- Chemerinsky, Erwin (2019). Ramble Law: Principles and Policies (6th ed.). New York: Wolters Kluwer. ISBN978-1-4548-9574-9.

- Ehrlich, Walter (1968). "Was the Dred Scott Case Valid?". The Journal of American History. 55 (2): 256–265. doi:10.2307/1899556. JSTOR 1899556.

- Finkelman, Paul (2007). "Scott five. Sandford: The Court's Most Dreadful Case and How information technology Inverse History" (PDF). Chicago-Kent Law Review. 82 (3): 3–48.

- Hughes, Charles Evans (1936) [1928]. The Supreme Courtroom of the Us. Columbia University Printing. ISBN978-0-231-08567-0.

- McCloskey, Robert G. (2010). The American Supreme Court. Revised by Sanford Levinson (fifth ed.). Chicago: Academy of Chicago Press. ISBN978-0-226-55686-iv.

- Nowak, John E.; Rotunda, Ronald D. (2012). Treatise on Ramble Law: Substance and Procedure (5th ed.). Eagan, MN: West Thomson/Reuters. OCLC 798148265.

- Vishneski, John S. (1988). "What the Court Decided in Dred Scott v. Sandford". American Journal of Legal History. 32 (4): 373–390. doi:10.2307/845743. JSTOR 845743.

Further reading [edit]

- Allen, Austin. Origins of the Dred Scott Case: Jacksonian Jurisprudence and the Supreme Court 1837-1857, Athens, Georgia: Academy of Georgia Press, 2006.

- Dennis-Jonathan Mann & Kai Purnhagen: The Nature of Wedlock Citizenship between Autonomy and Dependency on (Fellow member) Land Citizenship – A Comparative Analysis of the Rottmann Ruling, or: How to Avoid a European Dred Scott Conclusion?, in: 29:3 Wisconsin International Police Journal (WILJ), (Fall 2011), pp. 484–533 (PDF).

- Fehrenbacher, Don E., The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics New York: Oxford (1978) [winner of Pulitzer Prize for History].

- Fehrenbacher, Don E. Slavery, Law, and Politics: The Dred Scott Case in Historical Perspective (1981) [abridged version of The Dred Scott Case].

- Konig, David Thomas, Paul Finkelman, and Christopher Alan Bracey, eds. The Dred Scott Instance: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Race and Police (Ohio Academy Press; 2010) 272 pages; essays by scholars on the history of the example and its afterlife in American constabulary and society.

- Potter, David M. The Impending Crunch, 1848–1861 (1976) pp. 267–96.

- VanderVelde, Lea. Mrs. Dred Scott: A Life on Slavery'south Frontier (Oxford Academy Press, 2009) 480 pp.

- Fellow, Gwenyth (2004). Dred and Harriet Scott: A Family's Struggle for Liberty. Saint Paul, MN: Borealis Books. ISBN978-0-87351-482-8.

- Tushnet, Marking (2008). I Dissent: Not bad Opposing Opinions in Landmark Supreme Courtroom Cases. Boston: Beacon Press. pp. 31–44. ISBN978-0-8070-0036-half dozen.

- Heed to: American Pendulum II – 🔊 Mind Now: American Pendulum 2

External links [edit]

-

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource: - Dred Scott v. Sandford

- "Dred Scott Case". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Dred Scott Instance". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- Text of Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857) is bachelor from:Cornell Findlaw Justia Library of Congress OpenJurist Oyez (oral argument sound)

- The Dred Scott decision. Opinion of Primary Justice Taney, with an introduction past Dr. J. H. Van Evrie. Besides, an appendix, containing an essay on the natural history of the prognathous race of flesh, originally written for the New York Day-book, by Dr. Due south. A. Cartwright, of New Orleans. New York: Van Evrie, Horton & Co. 1863.

- Primary documents and bibliography about the Dred Scott case, from the Library of Congress

- "Dred Scott decision", Encyclopædia Britannica 2006. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 17 December 2006. www.yowebsite.com

- Gregory J. Wallance, "Dred Scott Decision: The Lawsuit That Started The Civil State of war", History.net, originally in Civil War Times Magazine, March/April 2006

- Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, National Park Service

- Infography about the Dred Scott Case

- The Dred Scott Instance Collection, Washington University in St. Louis

- Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice

- Dred Scott case manufactures from William Lloyd Garrison's abolitionist newspaper The Liberator

- "Supreme Courtroom Landmark Instance Dred Scott 5. Sandford" from C-Span'due south Landmark Cases: Historic Supreme Court Decisions

- Study of the Decision of the Supreme Court of the United States and the Opinions of the Judges Thereof, in the Instance of Dred Scott Versus John F.A. Sandford. Dec Term, 1856 via Google Books

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dred_Scott_v._Sandford

Posted by: camachowering.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Describe The Makeup Of The Supreme Court In 1857?"

Post a Comment